AP Syllabus focus:

‘Urban change can produce environmental injustice, including disamenity zones and zones of abandonment where hazards and disinvestment cluster.’

Environmental injustice and disamenity zones illustrate how uneven urban development exposes some communities to greater hazards, pollution, and disinvestment, shaping persistent socioeconomic and spatial inequalities within cities.

Understanding Environmental Injustice

Environmental injustice refers to the unequal distribution of environmental benefits and burdens, often affecting marginalized or low-income communities. It emerges when certain groups bear a disproportionate share of pollution, hazards, and inadequate infrastructure while receiving fewer protective services or amenities.

Environmental Injustice: A condition in which socially or economically disadvantaged communities experience greater exposure to environmental hazards and receive fewer environmental benefits than more advantaged groups.

Environmental injustice in urban areas typically results from political decisions, market forces, and historic planning practices.

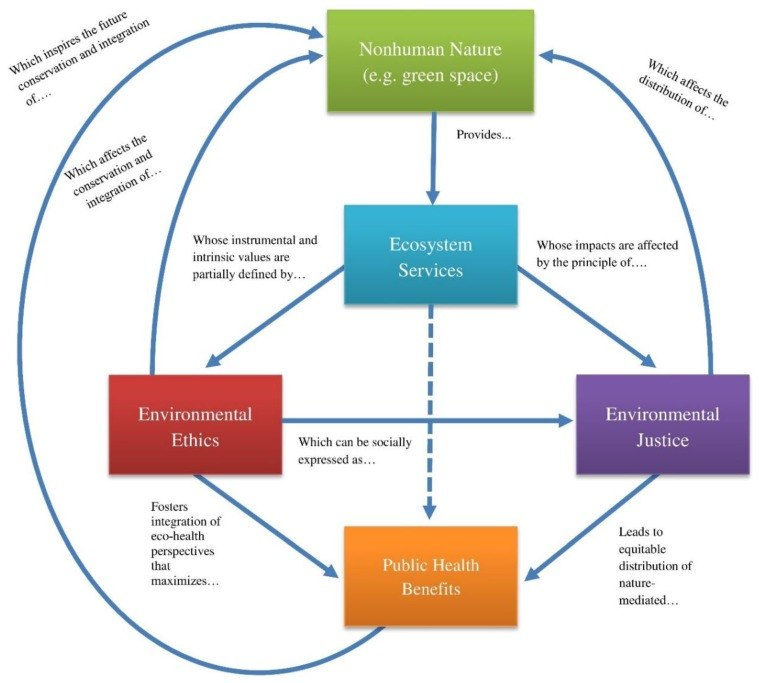

Conceptual diagram showing how nonhuman nature, ecosystem services, environmental ethics, environmental justice, and public health are interconnected. It emphasizes that the distribution of environmental benefits and burdens has direct implications for community health. The figure includes broader themes beyond the syllabus but helps situate environmental injustice within wider environmental-health systems. Source.

Disamenity Zones and Their Characteristics

Disamenity zones are urban areas with significant environmental or social drawbacks that reduce their desirability to residents or investors. These areas often exhibit low property values, limited public services, and proximity to undesirable or hazardous land uses. They may also overlap with zones of abandonment, where prolonged disinvestment leads to vacant buildings, crumbling infrastructure, and declining economic activity.

Abandoned residential buildings in Harlem, New York City, show how prolonged disinvestment can produce visible urban decay. This kind of neighborhood exemplifies a disamenity zone or zone of abandonment. The image focuses on structural deterioration rather than pollution sources but effectively illustrates spatial concentrations of neglect. Source.

Disamenity Zone: An area of a city characterized by undesirable environmental or social conditions, such as pollution, noise, or neglect, that discourage residential or commercial activity.

Disamenity zones reflect the spatial consequences of decisions about land use, transportation routes, and industrial placement. They highlight how some neighborhoods become trapped in cyclical patterns of decline.

Causes of Environmental Injustice and Disamenity Zones

Historical and Political Drivers

Redlining and discriminatory lending created long-term patterns of racial and economic segregation, concentrating minority residents in areas with fewer protections and lower investment.

Zoning decisions often placed industrial facilities, highways, and waste sites near low-income communities, reinforcing exposure to environmental hazards.

Fragmented governance across municipal and regional boundaries can leave marginalized neighborhoods without adequate representation or resources.

Economic and Market Forces

Land-value gradients tend to push undesirable land uses toward low-cost neighborhoods where residents have less political influence to resist them.

Urban disinvestment occurs when businesses and property owners withdraw capital, leaving vacant lots, failing infrastructure, and limited economic opportunities.

Industrial siting decisions frequently concentrate pollution-heavy industries in communities with lower land costs or fewer regulatory barriers.

Social and Demographic Patterns

Population decline in central-city neighborhoods can reduce tax revenues, limiting the ability to maintain infrastructure or provide environmental safeguards.

Migration patterns may shift lower-income households into zones more exposed to environmental risk because housing is more affordable there.

Systemic inequality ensures that environmental burdens accumulate where residents lack political leverage or financial capacity to relocate.

Spatial Patterns of Hazard and Disinvestment

Environmental injustice is often revealed in spatial patterns that cluster hazards in specific urban areas. Disamenity zones emerge where multiple stressors overlap, creating cumulative impacts on residents.

Typical Spatial Characteristics

Proximity to industrial corridors, rail lines, ports, or waste-processing facilities.

Concentrations of aging or failing infrastructure, including outdated water and sewer systems.

High levels of air and water pollution, noise, or traffic congestion.

Limited access to green space, clean water, or quality public services.

Patterns of vacant housing, abandoned factories, or crumbling streetscapes associated with long-term disinvestment.

These spatial patterns reflect how urban form and decision-making create uneven geographies of exposure and privilege within metropolitan areas.

Impacts on Urban Communities

Health and Environmental Consequences

Increased exposure to airborne pollutants, leading to respiratory illnesses, cardiovascular disease, and reduced life expectancy.

Higher risk of soil and water contamination, affecting drinking water and local food systems.

Greater vulnerability to flooding, heat islands, and climate-related hazards, intensified by inadequate infrastructure.

Social and Economic Impacts

Reduced property values and lower potential for economic development perpetuate cycles of poverty.

Limited access to amenities—such as parks, schools, and healthcare—hinders overall quality of life.

Persistent stigma attached to disamenity zones can deter investment, reduce political attention, and reinforce marginalization.

Political and Equity Implications

Marginalized groups often lack representation in planning processes, allowing undesirable land uses to continue accumulating nearby.

Uneven enforcement of environmental regulations can leave disadvantaged communities without adequate protection.

Inequitable resource allocation leads to infrastructure improvements and environmental amenities being concentrated in wealthier areas.

Urban Change and the Production of Disamenity Zones

Urban change processes—such as deindustrialization, suburbanization, and redevelopment—can reshape where environmental burdens are located.

Processes that Produce or Intensify Disamenity Zones

Deindustrialization leaves behind polluted industrial sites, abandoned buildings, and job losses that undermine neighborhood stability.

Suburbanization can divert investment away from inner-city areas, creating long-term infrastructure decline.

Urban renewal may remove blight in some places but displace vulnerable communities or shift environmental hazards elsewhere.

Infrastructure placement, such as highways or energy facilities, may benefit regional mobility while creating localized disamenities.

Urban change can therefore generate new forms of environmental injustice or deepen existing inequalities as hazards cluster in areas experiencing abandonment.

Addressing Environmental Injustice

Efforts to address environmental injustice focus on improving conditions, enhancing equity, and ensuring that marginalized communities have a voice in urban decision-making.

Key Strategies

Community participation in planning to ensure representation and transparency in decisions that affect environmental quality.

Targeted infrastructure investment in water systems, transportation, parks, and green space to reduce cumulative environmental burdens.

Environmental regulation enforcement to prevent hazardous facilities from disproportionately impacting low-income neighborhoods.

Remediation of contaminated sites to convert abandoned or polluted areas into safe and usable urban land.

Policies promoting equitable development, such as inclusionary zoning or environmental impact reviews sensitive to equity concerns.

These strategies aim to prevent hazards and disinvestment from clustering in specific neighborhoods and to foster more equitable urban environments.

FAQ

Planners often use early warning indicators to spot declining neighbourhood conditions. These include increasing vacancy rates, rising levels of reported environmental complaints, or repeated infrastructure failures such as burst pipes or power outages.

They may also analyse spatial data on investment flows, which can reveal areas experiencing sustained reductions in public or private funding. Community surveys help highlight early concerns about safety, noise, or nearby industrial activity.

Emergency services can inadvertently reinforce inequality when slower response times occur in marginalised areas due to ageing infrastructure, limited staffing, or poor road connectivity.

Improved fire, medical, and environmental hazard response can lessen the severity of environmental burdens by reducing risks associated with derelict buildings, illegal dumping, or industrial emissions.

Environmental contamination often remains long after industrial operations end, making redevelopment costly or legally complex. These brownfield sites may require extensive remediation before being reused.

Additionally, persistent stigma and low land values can deter new investment. Without targeted policy interventions, neighbourhoods may remain trapped in cycles of decay despite industrial decline.

Marginalised communities often occupy areas more vulnerable to flooding, extreme heat, or storm surges. These risks intensify the existing environmental burdens associated with disamenity zones.

Lack of green space, poor building quality, and inadequate drainage systems can make climate impacts more severe. As a result, environmental injustice becomes intertwined with long-term climate vulnerability.

Grassroots organisations may push for environmental monitoring, petitioning authorities to enforce pollution rules more strictly around vulnerable neighbourhoods.

Community mapping projects help residents document hazards, abandoned properties, or unsafe infrastructure. These data can strengthen campaigns for targeted investment, better public services, or environmental clean-up programmes.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain what is meant by a disamenity zone in an urban area.

Explain what is meant by a disamenity zone in an urban area.

1 mark: Basic statement that a disamenity zone is an undesirable or low-quality urban area.

2 marks: Clear explanation that it is an area with environmental or social disadvantages (e.g., pollution, noise, dereliction) that reduce its desirability.

3 marks: Full explanation including that such areas result from disinvestment or proximity to hazardous land uses and often experience declining property values or services.

(4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how environmental injustice contributes to the formation of disamenity zones in cities. In your answer, refer to both social and spatial processes.

Using examples, analyse how environmental injustice contributes to the formation of disamenity zones in cities.

Award up to 6 marks:

1–2 marks: Identification of environmental injustice as unequal distribution of environmental burdens affecting marginalised communities.

1–2 marks: Description of spatial processes such as clustering of hazardous facilities, ageing infrastructure, or proximity to industrial corridors contributing to disamenity zones.

1–2 marks: Use of relevant examples (real cities, neighbourhoods, regions) showing social factors, such as political marginalisation, low-income populations, or historical segregation.

Answers are credited for analytical links between injustice and disamenity formation (e.g., how planning decisions or lack of investment reinforce hazardous conditions).